Meeting the Watters'

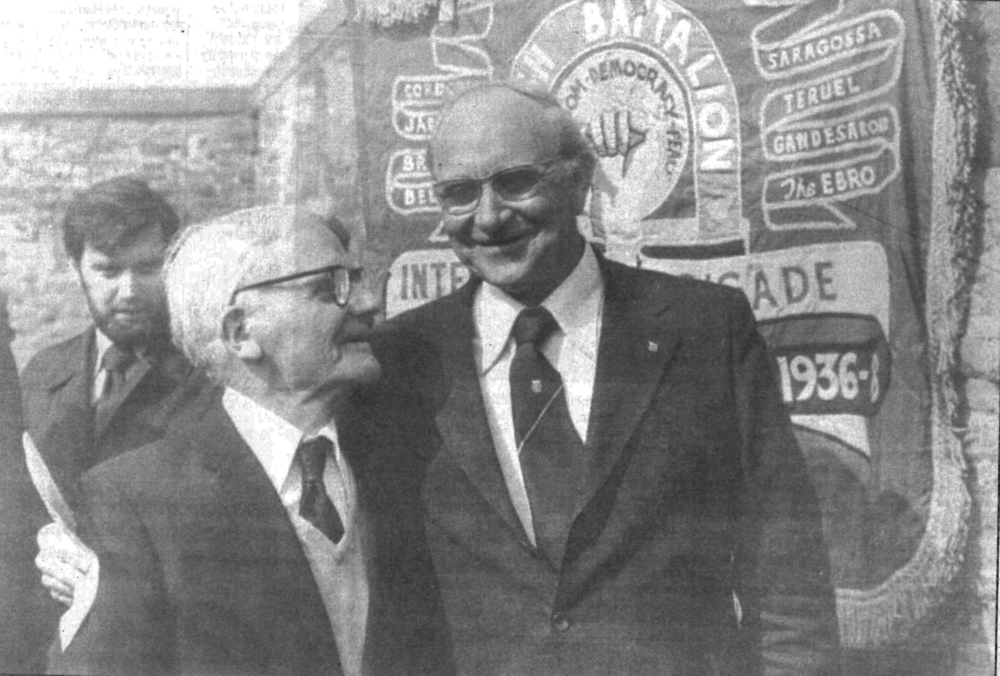

An image of George and his family taken in the 1930's

The prospect of meeting the family of George Watters had me slightly anxious to say the least. We had written a play about their father - and we hadn’t ever spoken with his relatives. I was about to meet the family of the man who boldly fought the fascists at their own meeting in in the Usher Hall, Edinburgh, by creating a “disturbance”, which swiftly broke into a riot. I was about to meet the family of the man who had never left Scotland but decided to travel to Spain, embarking on an eight hour trek over the Pyrenees to fight for a world he believed in. I was about to meet the family of the man who had been held in a fascist prison for almost two years continuously, only to fight again in WW2. Frankly, I was honoured.

The meeting place to me seemed obvious: the Prestonpans Labour Club. A working men’s pub in the heart of the town where the story of ‘549’ begins. Coincidentally, the club is also my old place of work. Hector, Jack and I each buy ourselves a pint of Tennents and sit down to wait. It dawns on me that I do not have a clue what any of George’s family look like.

After five minutes of waiting, watching the door and pint sipping, in walk four men, one wearing a T-shirt that states: “No Parasan”, a common battle cry of the Republican army during the Spanish Civil War. You shall not pass. We wave, and there’s an instant understanding from both parties; we were all in the right place.

We later find out that the T-shirt worn by Tam one of George’s sons, was purchased in Berlin from members of the German International Brigade memorial trust. For me, this is is yet another step in a deep realisation of the breadth and solidarity of the anti-fascist movement, and it resonates with me strongly.

Through our conversation we find out that George didn’t believe in war without a just cause and was not a fan of the poor working conditions and pay that came with working in the mines. He forbade his sons from ever going to war without a cause and from ever working in the pits. The next two generations would become miners regardless.

We discover that George had a common phrase when speaking about his time in Spain: “We didn’t fight for medals – we fought for our beliefs.”

One of George’s sons tells us about the fascist treatment of trade unionists in Germany, Italy and Spain. This makes me think of Thatcher’s treatment of trade unions in Britain.

We buy a second and then third pint, absorbed in a story about George’s fellow prisoner. The man broke down in tears; begging for his life. He was a prisoner about to be put to death at the hands the fascists. Refusing to let this happen, George stepped in, offering to take his place. He was told he had only a day to get his affairs in order. Only a day to prepare for death. George was saved only by his nationality and the political significance that it held during the conflict. We were moved to hear of his bravery and selflessness in what must have been a terrifying situation.

HIs family told us about the loving and supporting relationship George had with his wife and how she encouraged his involvement in the war. She stood by him. They tell us how she went door to door collecting money to “aid the lads in Spain.”

The family recount their colourful stories about George. A story teller, a friend and a family member. A caring, kind-hearted and articulate man. A politically engaged Communist from Prestonpans, who wore a badge with the symbol of a clenched fist until the day he died.